|

|

|

|

Pages:1

2 3 4

5 6 7

8 9 10

Next >>

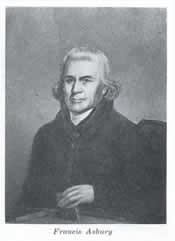

To attempt to record the mind of the founders and recapture the essence of the university's beginnings in the spring and summer of 1837 requires a vivid imagination as well as historical sensitivity. Preceding the advent of modern photography and the typewriter, the era is poorly documented by either written or pictorial materials and is also subject to the peculiar biases of that romantic and optimistic age. Moreover the story of the founding and first years of Indiana Asbury is part of the larger history of American higher education as well as of Methodism and its struggle to establish an educational system appropriate to its needs. Methodism,

which had begun in the 18th century as a movement within the Church

of England stressing personal piety and evangelistic fervor, was

led by an Oxford-educated Anglican minister, John Wesley, and quickly

spread to the British colonies in North America. By the close of

the American Revolution its adherents were numerous enough and its

leaders ready to organize as an independent religious body. On Christmas

1784, delegates meeting in Baltimore created the Methodist Episcopal

Church of the United States and named Francis Asbury as its first

bishop. Methodist circuit riders reached Indiana Territory by 1801,

and within 30 years Methodists comprised the largest single religious

denomination in the State of Indiana with an estimated membership

of 20,000.

Methodism

spoke to the spiritual needs of a frontier state where the prospects

for both material success and personal longevity were precarious.

For many, the teachings of Methodist Christianity provided a favorable

spiritual and moral climate to undergird the difficult task of

hewing out a new civilization in the wilderness. With its emphasis

on charismatic leadership the Methodist Church had initially frowned

upon formal education, and a number of early attempts to establish

its own colleges had only mixed success. But by 1820 a shift was

taking place in the thinking of Methodist leaders. A resolution

of their General Conference of that year recommended that local

conferences establish "literary institutions, under their own

control, in such way and manner as they may think proper,"

a measure reaffirmed four years later. Besides a number of academies

and seminaries successfully launched in the 1820s, a few Methodist

colleges began to appear in the next decade, beginning with Wesleyan

University in Connecticut in 1831.

The very first session of the newly created Indiana Conference in 1832 appointed a committee "to take into consideration the propriety of building a Conference Seminary." The committee's report, noting that most of the literary institutions were in the hands of other denominations, argued for the desirability of "an institution under our own control from which we can exclude all doctrines which we deem dangerous; though at the same time we do not wish to make it so sectarian as to exclude or in the smallest degree repel the sons of our fellow citizens from the same."

________________________________

What the Hoosier Methodist leaders were chiefly concerned about in the 1830s was the prevailing Presbyterian preponderance in the state's formal educational institutions. Not only had the rival denomination founded its own sectarian schools-the forerunners of Hanover and Wabash Colleges also constituted the dominant influence among the faculty and trustees of the publicly funded Indiana College founded in 1825, later named Indiana University in 1838. After a futile attempt to persuade the Indiana General Assembly to force the Presbyterians to share with the Methodists in the management and faculty of the state college at Bloomington, the Indiana Conference fell back on the notion of creating its own institution. Taking into account the continuing prejudice against formal education among many Methodists, there is justifiable confusion about what was really meant by such terms as literary institutions, seminaries, or colleges and universities-all still poorly defined in the American educational lexicon of that era. But clearly Indiana Methodist leaders were now ready to launch some kind of venture in higher education. Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Next >> |

Depauw University e-history | E-mail comments to: archives@depauw.edu

|

People, Events & Traditions

|