Pages:<<

Back 1 2

3 4 5

6 Next

>>

Appendixes:

Appendix A, Appendix

B

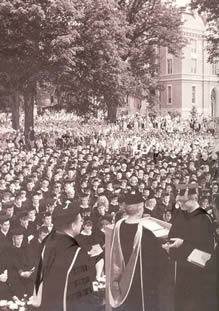

Despite

the remarkable transformation of DePauw University, especially during

the last one hundred years, DePauw students have remained largely

white, middle-class, and midwestern. Recent decades have seen important

changes in students' religious background, geographic residence,

and career patterns, but the social composition of the student body

and the patterns of student life have become perhaps even more homogeneous

and predictable since World War II.

During the first half of DePauw's history, the institution was relatively

small and recruited students chiefly from Indiana farms and small

towns. Total student enrollment grew steadily from just over 200

in the 1840s to about 400 in the 1870s. After the creation of the

new professional schools in the early DePauw years, student population

jumped to between 700 and 800 during the 1880s and 1890s. Only about

one-third to one-half of these students were engaged in college-level

work. The collegiate enrollment grew gradually from 50 students

in the 1840s, to just under 200 by the 1870s, to 300 students in

the 1890s, and around 460 during the next decade. Graduating classes

were even smaller with only seven students receiving degrees each

year in the 1840s, 16 in the 1860s, 45 in the 1880s, and 69 between

1900 and 1910. Small class size and the prescribed curriculum, which

insured that members of each class enrolled in the same courses,

maintained an intimate and personal social environment.

DePauw students in the 19th century had very similar backgrounds.

Probably three-fourths came from Methodist homes, and between 85

and 90 percent were Hoosiers, mostly from central Indiana. Antebellum

transportation was too expensive or, in many cases, unavailable,

preventing students from traveling long distances to obtain an education.

Students' families were part of Indiana's large rural and small-town

middle class that included successful farmers, shopkeepers, ministers,

lawyers, and doctors. Few were wealthy, even by 19th century standards,

but, as property owners, they enjoyed financial security and social

respectability and held positions of leadership in their communities.

Early DePauw graduates overwhelmingly entered the professions, just

as the northern middle class was shifting from property ownership

to education and professional training as the main basis of its

membership. Despite the university's close Methodist ties, only

one-fourth of its early graduates became ordained ministers. Of

all graduates between 1840 and 1905, in fact, just 16 percent were

ministers or missionaries while 22 percent were educators and 18

percent lawyers. Such a relatively low proportion of alumni in the

ministry may seem surprising for a 19th century church-related university,

but it clearly reflects the secular career orientation of its students

as well as the fact that most Methodist churches still did not demand

a highly educated leadership. Only 11 percent of the pre-1905 graduates

went into business, a career that eventually became much more attractive;

around one-fourth of the members of each class after 1910 found

employment in business and finance. Female graduates who sought

careers generally became teachers.

DePauw not only promoted its graduates' social mobility but also

trained leaders for the midwest's rapidly developing commercial

and urban society. A DePauw degree also enhanced geographic mobility.

Almost 65 percent of the 1900 and 1901 graduates were from Indiana,

but by 1920, only 42 percent still resided in the state and 23 percent

were living outside the midwest. By the 1950s, about half of the

alumni were no longer midwesterners.

Nineteenth-century DePauw students probably came from a broader

social base than is true today. Early DePauw was a remarkably open

institution. There was no tuition, and incidental fees were only

$24 per year in 1900. A room could be rented for $20 to $30 per

year and board was $2.50 per week. The college catalogues claimed

that $200 was sufficient to obtain a year's education at DePauw.

Many students, in fact, were self-supporting and financed their

education by taking odd jobs in Greencastle during the school year

and through summer employment.

Back

to Top

Pages:<<

Back 1 2

3 4 5

6 Next

>>

Appendixes:

Appendix A, Appendix

B

|

![]()